Simon Turner, Head of Content, InvestmentMarkets

10 June, 2024

Most of us have been taught to diversify our investment portfolios to ensure we remain on track to achieve our investment goals, regardless of a few mistakes and bear markets along the way.

Intuitively, diversifying makes sense to most people as a concept. Even in the seventeenth century, it was written in Don Quixote: ‘It is the part of a wise man to keep himself today for tomorrow, and not venture all his eggs in one basket.’

This lesson has been well learnt by the world’s investors since then. But maybe it has been too well learnt. We size up diversification versus its twin sibling with opposing intentions, deworsification, below.

The theory behind diversification

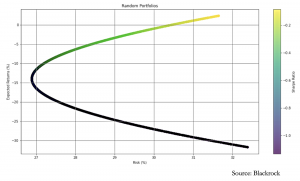

The theory behind diversification is built upon the concept of the efficient frontier, the set of optimal investment portfolios which maximise returns per unit of risk:

According to the efficient frontier theory, by creating sufficiently and optimally diversified portfolios investors can maximize their risk-adjusted returns. In other words, all portfolios lying below the efficient frontier are sub-optimal since their returns are not adequately compensating investors per unit of risk.

If this theory is correct, the number of stocks in a portfolio is of vital importance for investors’ future returns.

Case study in the benefits of diversification

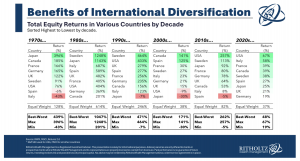

The performance of the equities in various countries provides a pertinent case study in the benefits of diversification.

After the seemingly relentless global outperformance by the US equity market over the past decade a half, it’s easy to forget that this state of affairs has not always been the case—as shown below:

Due to investors’ tendencies to overweight recent experience in their expectations of the future, otherwise known as regency bias, many investors are currently overweight the US in their portfolios.

Regency bias is sometimes quoted as an argument in favour of diversification. Despite the US market outperforming all other markets in recent years, a diversified portfolio would be exposed to a range of geographic regions in the knowledge that the US market’s recent outperformance is unlikely to provide an accurate guide of future returns. A geographically diversified portfolio is more likely to be positioned to weather a change in global market leadership as and when that occurs.

The problem with diversification

As with all theories, the efficient market frontier works beautifully in a spreadsheet, but it’s harder to translate into real world investment advice.

For starters, no one’s going to present you with a real world efficient market frontier which accurately guides you in terms of the perfect number of stocks and the ideal weighting per stock to optimize your returns.

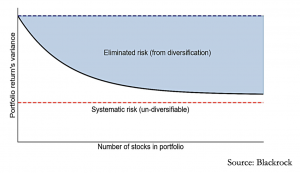

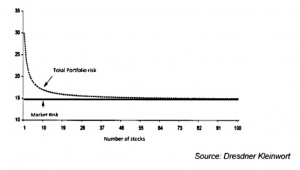

Diversification also has its limits in terms of risk reduction. Whilst investing in a diversified portfolio of uncorrelated assets is sometimes helpful at reducing portfolio volatility, beyond a certain number of stocks there’s a diminishing risk-reduction impact of adding more assets to a portfolio—as shown below.

So beyond the diversifiable risk, what we’re left with is systemic, or un-diversifiable market risk. This is the risk which is inherent to investing in listed assets in the connected, global financial system.

Enter deworsification

So we’ve established that diversification can help reduce portfolio risk … up to a point.

We’ve also established that there’s a bucket of systemic risk that we can’t address with diversification.

What we haven’t yet established is the magic number of stocks in a portfolio at which diversification doesn’t only stop helping a portfolio, but starts to hinder returns. This magic number is the point at which diversification morphs into deworsification. It’s when our efforts to reduce our risk begin to hinder our risk-adjusted returns (return per unit of risk).

As such, it’s important we know what the magic number is and remain roughly in line with it if we are to avoid the return-eroding impacts of deworsification.

So what’s the magic number?

Let’s start with the theory about this magic number. A 1970 study by Fisher and Lorie established the notion that 95% of the benefits of diversification can be attained by owning a portfolio of 30 stocks.

Since this research was completed, similar studies have roughly backed up this finding.

At this point, we need to look beyond the theory for a guide from successful investors with real world experience.

Legendary investor Peter Lynch doesn’t concur with the above-mentioned research. In his book One up on Wall Street, he wrote: ‘Owning stocks is like having children – don’t have more than you can handle, five to eight is plenty.’

Some investors may be surprised to hear this.

Charlie Munger had an even more extreme view on the subject. A few years ago, he admitted to an audience of investors that he held only three investments in his family portfolio: Berkshire Hathaway, Costco, and a mutual fund run by Himalaya Capital. Not only that. Charlie also confessed he believed that university professors who recommend owning at least 30 stocks were ‘dispensing balderdash’.

So the obvious question is: why do financial theory and the experience of successful investors diverge so dramatically on this subject?

One explanation is that successful investors are much better than average at mitigating their risks by picking successful businesses which are destined to outperform over the long term. In contrast, financial research tends to focus on entire indices of stocks which include many stocks successful investors like Peter Lynch and Charlie Munger would regard as un-investible. Hence, we’re comparing apples with oranges.

Investors surf a fine line to optimize returns

So financial theory gives us a magic portfolio size number of 30 stocks, whereas two investing legends advise five to eight stocks and three stocks respectively.

For an individual investor who isn’t investing full time, meeting somewhere in the middle is likely to prove prudent and fruitful. For example, a portfolio of 10-20 stocks is likely to provide the benefits of diversification without roaming into the realms of deworsification.

It’s a fine line all investors need to learn to surf if they want to optimize their long term returns.

Originally published on InvestmentMarkets