The Disposition Effect

Why selling losers and letting winners run is hard to do

Author Daniel Grioli, first published in EQUITY, February 2017

We are all prone to behavioural biases that affect our judgment. That’s the bad news. The good news is that we can significantly improve our results by sticking to an investment strategy that helps us to reduce the number of costly mistakes that we make.

But first we need to identify our mistakes. Academics Brad Barber and Terrance Odean[1] describe the errors that individual investors commonly make…

They trade frequently and have perverse stock selection ability, incurring unnecessary investment costs and return losses. They tend to sell their winners and hold their losers, generating unnecessary tax liabilities. Many hold poorly diversified portfolios, resulting in unnecessarily high levels of diversifiable risk, and many are unduly influenced by media and past experience.

Some of these errors are more subtle than others. For example, it may not be immediately obvious that selling shares that have increased in value since bought (winners) and holding shares that have decreased in value since bought (losers) is a bad idea. After all, it’s commonly said that “nobody ever went broke taking a profit”. But is this always true?

Here’s two reasons why being quick to sell and take a profit may not be such a good idea. First, truly great companies are hard to find. Just how rare are they? You may be surprised by the answer. A long-term study[2] (1983 – 2007) of the largest 3000 stocks listed in the United States found that:

- 39% of stocks had a negative lifetime total return (2 out of every 5 stocks are a money losing investment)

- 18.5% of stocks lost at least 75% of their value (Nearly 1 out of every 5 stocks is a really bad investment)

- 64% of stocks underperformed the Russell 3000 during their lifetime (Most stocks can’t keep up with a diversified index)

In other words, most of the stock market’s performance can be attributed to the performance a handful of truly excellent companies that have been able to grow over time by re-investing retained earnings in profitable business opportunities.

So what’s the lesson? Great investments are hard to find. If you’re lucky enough to own one of these companies then you should really think twice (maybe even three times) before selling.

The best way to illustrate this is with an example. In his 1995 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Warren Buffett wrote about an investment in Disney…

I first became interested in Disney in 1966, when its market valuation was less than $90 million, even though the company had earned around $21 million pre tax in 1965 and was sitting with more cash than debt… Duly impressed the Buffett Partnership Ltd. bought a significant amount of Disney stock at a split-adjusted price of 31 cents a share. That decision may appear brilliant, given that the stock now sells for $66. But your Chairman was up to the task of nullifying it: in 1967 I sold out at 48 cents.

Buffett had found an excellent company in Disney; but he took a quick 55% profit only to miss out on a 21,290% gain (not counting dividends)[3].

Second, selling winners is tax inefficient. Selling a winning stock triggers a capital gain. For tax purposes, investors should postpone paying tax by continuing to hold their profitable investments. Instead, they should capture tax losses by selling their losing investments.

What about holding onto losers? Many investors reason that it’s only a “paper loss” if you don’t sell, as opposed to a realized loss if you do. Besides, there’s always a chance that the stock’s value might recover.

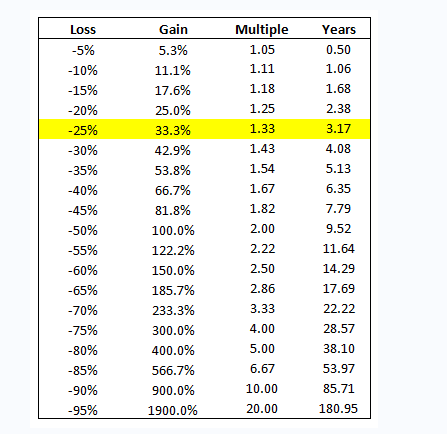

This faulty reasoning ignores the mathematics of loss illustrated in the table below. Here’s how to read the table: to breakeven after a 25% loss, an investor requires a 33% gain (highlighted in yellow), or a gain that is 1.33 times the size of the loss. If we assume that the loser goes on to perform in-line with the long-term average for Australian shares (from 1987 through to 2016) then it would take 3.17 years to break even.

The negative effects spiral rapidly out of control once a loss exceeds -25%. For example, an investor holding a stock that has lost 70% of its value requires a gain of 233% just to break even – that’s over 22 years worth of share market gains!

The Mathematics of Loss

The mathematics of loss highlights the need to deal with losses before they get out of control. Why is this so hard to do? The tendency to sell winners and to hold onto losers is deeply ingrained in investor psychology. For example, the stockbroker Gerald M Loeb wrote in 1935[4] :

Cutting losses is the one and only rule of the markets that can be taught with the assurance that it is always the correct thing to do… But, as a matter of actual application, it requires a completeness of detachment from human frailties which is very rarely achieved. People like to take profits and don’t like to take losses. They also hate to repurchase something at a price higher than they sold it. Human likes and dislikes will wreck any investment program. Only logic, reason, information, and experience can be listened to if failure is to be avoided.

Academics refer to the tendency to sell winners and hold losers as the “Disposition Effect”. The name comes from the title of an academic paper written by professors Hersh Shefrin and Meir Statman in 1985 entitled The Disposition to Sell Winners Too Early and Ride Losers Too Long: Theory and Evidence. In it, the authors identify 4 possible explanations for the disposition effect, they are:

Prospect theory – Developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky[5] , prospect theory predicts that the pain of loss is felt roughly twice as strongly as the joy associated with a gain. The theory also predicts that we focus on our change in wealth, relative to a fixed reference point (e.g. the price at which the purchased a share), rather than our overall level of wealth. It also predicts that we often take less risk when trying to protect a gain (e.g. by investing in “sure things”) and more risk when trying to avoid a loss (e.g. by “doubling down”).

Regret aversion –Selling at a loss (even though the after-tax return is higher) means admitting that we were wrong. Meanwhile, holding the stock allows us to avoid the regret that comes with admitting that we’ve made a mistake.

On the other hand, holding onto a winning stock means risking the profit that we’ve already made. If the stock falls we’ll kick ourselves for not taking a profit when we had the chance. Meanwhile, taking a profit creates the feeling of pride, even though it lowers our after-tax return.

Mental accounting – We open a new mental “account” each time we purchase an investment. We then focus on the performance of each account, rather that the performance of our portfolio as a whole. This is known as narrow framing. Shefrin and Statman suggest that selling a losing stock is hard to do because we perceive this as closing our mental account at a loss.

Self-control issues – The rational part of us may know that selling winners and holding onto losers is the wrong thing to do and yet we often struggle to take action. In other words, we don’t have enough self control to sell our losers. We also find it hard to resist the instant gratification that comes from selling a winner.

Just how large an impact does the disposition effect have on investor behaviour? Terrance Odean (1998) examined the trading records of 10,000 individual accounts from one of the largest US discount brokerage over the period from 1987-1993. He found that 60% of all sales were winners, while 40% were losers. In other words, investors realized their gains at a 50% higher rate than their losses. The larger the gain or loss, the stronger tendency to sell winners and hold losers.

Research into the behaviour of individual investors in other countries has yielded similar results. “The disposition effect is a remarkably consistent and robust phenomenon.”[6]

Even professional investors are prone to selling their winners and letting their losers ride, although they do appear to be less prone to the disposition effect than individual investors. This suggests that it is possible to learn how to manage its influence on our decision-making. That is a topic for another article.

[1] Barber and Odean, The Behaviour of Individual Investors, 2013: http://faculty.haas.berkeley.edu/odean/papers%20current%20versions/behavior%20of%20individual%20investors.pdf

[2] The Capitalism Distribution, BlackStar Funds: http://www.theivyportfolio.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/12/thecapitalismdistribution.pdf

[3] Disney (DIS) trades at $108.98 as of 8/1/2016

[4] Loeb’s book The Battle for Investment Survival first published in 1935 sold over 200,000 copies during the Great Depression.

[5] For more information on prospect theory please see my article in the November 2016 edition of EQUITY magazine: https://www.australianshareholders.com.au/equity-magazine/2016

[6] Barber and Odean, The Behaviour of Individual Investors, 2013